Getting to the Start

The challenge this year is to Newport, Rhode Island, USA. I have been

getting Louisa ready for this over the past 12 months and getting her ready for

offshore passages for the preceding 12 months. The final preparations have been

stores for the 50 days I expect it to take me plus a contingency. If things get

desperate I reckon I can stay out for 80 days at a push but this really will be

a stretch. I have lists for everything; food, water, jobs, clothes etc. Every

single space on the boat is in use and she feels heavy.

Monday 25th April I set off, two friends take me out for dinner in Rochester before ferrying me out to Louisa. First problem, the bank has declined the direct debit for the satellite tracker. I was hoping to have a quiet night aboard before an early start but instead I spend it with phone and computer trying to change the bank details on a most unfriendly Garmin portal.

When I do get away I set off just before the tide and into the wind. At Margate I anchor off for the tide change and get some rest. When the tide does change I make it to North Foreland before the wind is in my favour. I spend the next 24 hours roaring along until I reach the Solent and anchor in Bracklesham Bay to await the tide into Langstone Harbour where I anchor up and rest for a couple of days. Then it is into Gosport to visit my mother and sister.

I leave Gosport into a good breeze

and make it to Keyhaven where again I wait for the tide. At midnight I set off

with no wind and motor to the river Dart. 17 hours, 18lts of diesel used and by

8PM I am moored up to a visitor buoy as I fail to find my preferred anchor

spot. I pass Denis Gorman’s old boat, Lizzie G, Albin Vega. It is a stark

reminder of how life has to be lived. The river is far fuller of moorings than

I remember but the next day, after being relieved of £30, I set off for

Plymouth. I sail and motor up to the Lynher River where I anchor until I am

ready to head to the Mayflower Marina and meet up with the others. After a

couple of nights rest I make my way to Mayflower to join in. The others are

already there and we have a very pleasant couple of days including being

interviewed by a young couple who have a YouTube channel, 2:40 in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vhbmNP4x8ho&t=560s if

you are interested.

Weather

About halfway through the passage my wife and I were text chatting on

the satellite communicator and she mentioned that all I talk about was the

weather. THAT IS ALL THERE IS, everything is the weather; what progress I make,

what gets broken, how I feel, what are my plans, they are all the weather.

Weather information

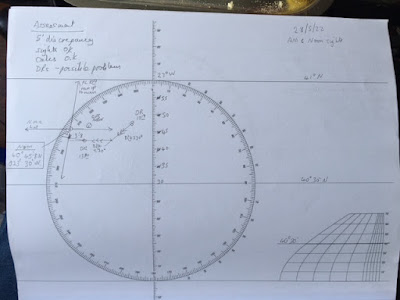

The image above was from 29th May

and through interpretation with the predictions it became possible to work out

bigger picture forecasts for where I was. Below is a predictive chart for the

day before but produced on 26thMay.

At my location to the north east of

the Azores the weather was NW’ly F3 and the front was clearly visible as cloud

formations and wind backing to SW.

In hindsight I wish that I had spent

more time practicing and learning how to make the most of this resource.

Reception in the UK isn’t great because of being too close to the transmitters

and background noise but even with these factors images are still usable.

This image, probably the poorest of

the passage, is the analysis conducted by DWD on the Atlantic on 7th June

while I was in port, TS Alex is just North of the Azores and there is another

low on the North Norway coast. (I think the reason it is so poor is because a

boat nearby arrived and the interference levels increased.)

My ideal reception schedule, this

became my daily routine.

Hamburg

08:17 H+36 surface pressure 13881.2 kHz

08:30 H+48 surface pressure 13881.2 kHz

11:50 surface weather 06h 7878.6 kHz

17:36 surface weather 12h 13881.2 kHz

19:00 surface pressure analysis 13881.2 kHz

19:34 H+24 surface pressure 13881.2 kHz

Northwood

10:00 surface analysis, no isobars, 8038.7 kHz

13:00 surface pressure 8038.7 kHz

13:12 H+24 surface pressure 8038.7 kHz

All times BST, all transmissions USB

I much preferred the DWD charts from

Hamburg but Northwood was usable.

2. Garmin

inReach

One of the services offered through

my Garmin inReach subscription is weather forecasts. These range from simple

local two day pictograms, through more detailed longer range up to their marine

version. The marine version costs extra and includes sea state predictions

which was useful but I found that weatherfax could provide the swell / wave

height info. The really useful info was the swell period. Anything below 10

seconds and it was getting uncomfortable.

This image was from 16th May

and was fairly typical. The swell did get up to about 6m and the period was

around 7 seconds so fairly rough. Wind speed peaked at F8 SW on 16th by

my reckoning.

3. Shore

support

I was blessed with fantastic support

from someone who has been through these same conditions so understands what it

is like. The support was far more than wind speed and direction. It

was motivational, empathetic, focussed and very timely. I might quibble about

how accurate Windy’s wind speed predictions are, about 50% low, but just having

someone looking out for me was tremendous and got me through a dark patch.

Weather As Found

First day was a SE breeze which

enabled me to put in the best day’s performance of the passage, 99nm. Then we

hit the edge of the first system! It had been stuck off the UK for the past 48

hours and the sea state was 9m with a period of 12 seconds. With wind waves on

top it was very uncomfortable causing random slamming and all but stopping

forward progress. I turned round headed south and tried again. My log record

says F6 SW, 2 reefs but I couldn’t get a suitable sail balance. 3 reefs was

better and by the next day the wind had veered to NW F3 but the sea state was

the issue, I made 27nm on the third day in the wrong direction. Things didn’t let

up and it knocked the stuffing out of me and loosened a few fillings on me and

the boat. Then the wind died and I was becalmed in the bay of Biscay for a

couple of days. By day 7 the second weather system was upon me and for 4 days

of triple reefed bashing into big seas but only managing 80° off

the wind progress was very slow and by day 12 I was only ½ way between the UK

and the Azores.

I had always intended to take the

southern route and was aiming for 40N, 30W but couldn’t make this heading most

of the time. Winds were south westerly for around 80% of the time and more

often than not F6 or more. It was around this time I found I had a problem with

the rigging so decided two things, sail very conservatively, i.e. more reefed

than necessary, sheets not hard in and douse sails if slamming. Secondly, go to

Azores to check things out.

Weather system 3 was upon me by day

15, it would have been reasonable to expect to be within striking distance of

the Azores by now on a normal passage but I was over 500nm from Terciera. The

latest weather system brought F7, gusting F8, NW’lies so at least I could make

progress in the right direction, albeit with about 1.5m of jib set and main

lashed to the boom.

I then had a really good day on day 19

with multiple dolphin sighting (where do they go when it is rough?) and 74nm

progress in the right direction. F3 NNW with triple reefed main and genoa was

ideal for what I wanted. Dolphins at night were incredible, setting off

phosphorescent streamers all round the boat and making a lot of noise. Of

course the photos were totally dark but this was the highlight of the trip. By

now the wind direction had been steady enough for the sea state to build up and

so things started to get uncomfortable again.

Once that system had passed I was on

the edge of a high pressure system so with F1 SSE winds I made the most of it

and had my second best mileage of the trip, 82nm. By day 23 I was in another

system, number 4 for the passage, and spent most of it with just a very small

jib and no main. It looked like I might make Praia do Vitória but the wind

backed and pushed me south. The barometer was falling quite rapidly and the weatherfax

was showing a deepening depression. This flattened out at 994mb so not bad at

all. I still had F7 gusts keeping me on my toes and I hand steered all night to

try for Terceira. The wind had backed to NW and so I resigned my self to

missing Praia do Vitória and instead trying for Angra do Heroismo. On day 25 I

had to motor for a few hours against the NW F5 to close Angra and as the lee of

the island took hold the wind abated and I made the anchorage at first light.

25 days is probably one of the slowest

Jester passages to the Azores and 4 weather systems in 3.5 weeks seems a lot

for this time of year. None of the systems generated storm conditions but they

did generate gales. I hove to during these but didn’t deploy a sea anchor and

didn’t feel the need to. Due to the rigging problem I sailed the second half

very cautiously. The great circle distance is 1,218 nm, my midday to midday

totals was 1,378 nm and my satellite tracker based on 4 hourly positions was

1,879 nm. I probably travelled close to 2,000 to get the Azores and of the 25

days, only three were fine sailing days. The others were mostly poor because of

sea state or I was becalmed. Sea state was the biggest factor, especially once

I had found the problem with the rigging. Any 24 hour period of steady wind

direction would cause the sea to become an issue. Similarly, a significant

change in wind direction would knock the sea state back so fronts, especially

cold ones, were things to look forward to. Much of this seems contrary to

standard model weather; it is rough in Biscay, I was becalmed for

almost 2 days. The Azores high can be relied upon, there were

multiple sub lows that formed over the Azores and joined the main lows.

Named storms are formed later in the season. Just after I arrived in the

Azores Tropical Storm Alex formed over Bermuda and at one point was forecast to

bring storm force winds to the Azores and to the UK.

Now the difficult bit, I have to get

home through this!

Preparations

Boat Preparations, “The hardest part is getting to the start line”

Summary of this blog so far, I bought Louisa from a couple at MCC for whom this was the wrong boat. It was largely set up for offshore sailing with numerous features that they had no concept of; self steering wind vane system, strengthened bulkhead under the mast, sea cock on the exhaust outlet, rope and sail locker in place of a berth and spare forestay with strengthen deck eye to mention some of the obvious features.

It still took me 2 years, with almost a

year out for covid and associated restrictions to get ready. This included;

1. new

sails

2. AIS

3. Short

Wave radio and antenna

4. Lee

boards

5. Gimballed

spirit cooker

6. Additional

bilge pump

7. New

lower shrouds – see problems!

8. New

running rigging

9. Side

locker netting

10. Main halyard winch in coach

roof

11. Additional sheet winches for

downwind sail handling

12. Life raft on coach roof

13. EPRIB, Sat tracker,

14. Solar power

15. Split power distribution

16. Storm jib

17. Jack stays

18. Companionway ‘shower

curtains’

In all about 130 changes, some of which were improvements and some just because I wanted to.

Things I had hoped to do but hadn’t included; not enough sea miles, not enough range of sailing conditions, no overnight offshore sailing and practising emergency drills. I had a list of them and the actions in bullet form.

Things I wish I had done

1. Companionway

seat

2. Black

mould problem

3. Replaced

the coach roof handrails

4. Checked

the boom more carefully

5. Boom

preventer

6. Chaff protection

Considering the lack of sea time and covid, things worked out very well. The damages were limited to the steering compass that lost it’s damping oil and light after I fell on it and the lower shrouds which were a classic case of cutting too many corners and then not seeing the rectification through. This one problem caused me the most grief and worry. It took about 2 hours to fix in Angra with the parts I had onboard.

Personal Preparation

I mainly prepared by making lists of everything I could think of and then either tackling them or adapting things to reduce their impact. Food planning involved me with a set of scales in the kitchen cooking rice and pasta until I knew the working proportion of water to starch. For pasta it is 2:1 by volume pasta to water and a beaker of pasta (plus ½ beaker of water) is enough for two days. With rice it is 1:2 by volume rice to water. ½ a beaker of rice cooked with 1 beaker of water is sufficient for 2 meals. But the rice usually turned to mush so I opted for ready cooked rice.

Calorie intake was also considered. I

reckoned on 1,500 kcal per day + a few sweets. This is below my normal intake

by a considerable margin so I was expecting to lose some weight.

Daily diet

Breakfast

Cereal bar (199kcal)

Oat cakes (300kcal)

Cuppa (0kcal)

Lunch

6 Rivita (200kcal) OR couscous (380kcal)

Choc spread (100kcal) OR Can sardines (160kcal)

Slice fruit cake (132kcal)

Cuppa (0kcal)

Dinner

1/2 Tin of curry / chilli (196kcal)

1/2 pack rice (168kcal)

OR

Tin soup + TVP

Cuppa (0kcal)

5 sweets (100kcal)

Evening

Mars bar (150kcal)

I loaded the boat with sufficient supplies for 80 days, this was based on 50 days to USA + 30 day contingency in case I had to leave promptly, such as for changed covid restrictions. For water I loaded 180 litres on the same basis. This was stored in various containers spread around the boat.

Sleep for me has never been an issue offshore as I don’t sleep particularly well and can manage for extended periods on napping and resting. I had tried a vitamin supplement that was supposed to help but couldn’t tell any discernible change so dropped that idea.

For fitness I relied on walking, I live in a hilly area of countryside so could do quite a bit and tried to do it at pace. It was adequate.

Strength, I did nothing and had adequate for everything I needed to do. I did try flexibility exercises and practicing Asian squats but neither to any avail. Losing weight made me more flexible as did basic movement around the boat.

Mental fortitude, I prepared several strategies for the drop in motivation that I expected. What I didn’t expect was that the drop would be so steep and almost none of my strategies could be activated or implemented due to the conditions on board. The boat movement made all but lying in my bunk or basic boat management all but impossible. What did help was having shore support. A very simple message, not motivational in any regard, helped me through a dark patch without the sender realising it.

Health – I have a couple of minor health issues in the run up to departure, I pulled a muscle in my shoulder in early 2020 and finally got physio for it in late 2021. It was OK but still a concern when I set off. Since setting off it has not given me any problems and is cured. Having suspected covid, again in early 2020 before testing became an option, caused a few weeks of flu like symptoms and after effects. The longer term issue was stamina and possibly related is a loss of sense of direction. I have always had a good sense of direction and can transpose a north up display onto a head up display in my mind’s eye without a problem. Now, however, I struggled to relate targets on my AIS to their location around me and converting true wind direction into apparent also required concentration. In 2019 I pulled my Achilles tendon. I had driven to meet a client and when I got out of the car I could barely walk. This still niggles me and while I haven’t had any professional help with it I do regular stretching exercises and these seem to help but are harder to do on the boat. For a 60 year old man who doesn’t have a health regime I don’t think this is too bad. None of it hampered my sailing.

Money – to enable home life to continue and reduce my stress levels I needed to ensure that all bases were covered for up to 6 months. This was primarily achieved by standing orders and having suitable reserves in the appropriate accounts. I had budgeted £2,000 for living costs during the adventure after pre-payments for things like insurance and satellite communications had been taken care of.

Business – to shut down business operations for 6 months, even though I’d probably only be away for 4 to 5 months was made very easy by my primary sources of income who both wished me well and suggested I contact them upon my return. I already had work booked in for my return from another source so this also contributed to reducing my financial concerns. Someone I met on my trip summed it up, “you know you can do it but your just not quite sure when”. Or to put it another way, if not now, when?

Home life – the few activities that are solely mine at home include the cars and cutting the grass. We got an electric lawn mower and car break-down cover. Almost everything else fell to my wife, as it happened she became a plumber and was already a decorator.

Communications – I wanted to stay in communication with a wide variety of people and this proved to be the most difficult element. The Challenge organisers and sailing community wanted to know the details. My family and I wanted an element of family life to continue and my mother and aunt wanted to know I was safe. Non sailing friends and work colleagues might or might not be interested but were probably not conversant enough with the environment I was going to be in to relate to the information I might post. To tackle this I set up two groups; one who would be able to message me, the other who would only be able to see my general posts. This situation worked OK but there was a point when the challenge organisers received information and posted it on the challenge web site even though I hadn’t let my family know. The information referred to a potentially serious problem with the boat, the lower stays had lost tension. Nothing anyone ashore could do to help but information some would find very interesting and others would find very worrying. Luckily the organisers took it off the web site before the worry kicked in. The two biggest factors in communications was being able to stay in touch with home life and getting support from ashore. The shore support was mainly weather related but turned out to be motivational as well.

So was ‘the hardest part getting to the start’? So far the hardest part was the passage to the Azores. As very little of the preparation prevented me from getting to Newport with the possible exception of the rigging issue which I fixed in the Azores and probably accounted for about 15% of the time at sea getting to the Azores, I don’t think this stopped me.

What would I have done differently is

very hard to identify at this stage. I should have completed the work on the

rigging and some more sea time would have been useful. It will have to wait

until I get home and have made a proper assessment of the trip before I’ll be

able to say if I did the right preparation.

Navigation

The passage plan I had identified is termed the southern route. In theory this avoids the heavy weather on the shorter great circle route where the Atlantic depressions run against the direction of travel. The great circle route also has the strong possibility of ice and fog banks off Newfoundland. I don’t like fog, I am terrified of ice and I prefer slightly warmer, not hot, weather. There is a mid route but unless the boat you are on is low displacement such as a multihull, the gulf stream can account for up to 30% of boat speed for the final third of the passage. The southern route is about 700nm longer than the great circle route and the plan was to sail south west to 40N and then west south west below the gulf stream until south of Newport then head north to cut across the gulf stream at its narrowest point. So with this in mind I set off in a south westerly direction, problem was that the weather was moving from the south west towards the UK and a day out of Plymouth I reached the edge of a depression that had been sat off the UK for the previous 48 hours. The sea state had built up and heading south west was not an option. Between heading north west or south I opted for south. This took me into the bay of Biscay which I had been hoping to avoid but it turned out to be calm, I was becalmed for two days in the bay. To get back on track I tried heading west again but further weather systems pushed me south.

Navigating to way points on an ocean scale was new to me and I tried to keep in mind that 100nm off track is irrelevant if that is where the weather puts you. I use my Matsutec AIS navigator to monitor progress towards way points and on this passage it kept me on track through a combination of range reduction and course to steer changes. I opted for the heading that I could achieve that caused the range to reduce and if this put me into heavier weather then I opted for increasing bearing. Increasing bearing has limitations as it is very slow to respond over the ranges in question. By setting sub waypoints at shorter ranges this became more usable. After the third weather I was able to make progress in the desired direction, albeit I would have preferred to have been level with the Azores by now.

As luck would have it a friend had

lent me his spare Azores pilot book so I had no qualms about navigating to the

Azores, I had downloaded Navionics for the Azores as well. Anyone who knows me

will appreciate that the Azores has far more appeal to me than almost anywhere

else. So I changed plans and headed for the Azores. The passage making became

easier as did almost everything with the exception of my worries about the

rigging. There was a final sting in the tail, the fourth weather system of the

trip caused me to divert to Angra do Heroismo instead of Praia do Vitoria which

had been my preferred port. This was the final nail in the coffin of thoughts

of Newport. When I was in the lee of Terceira I turned the engine on and

motored the final 10 miles into the anchorage at Angra and promptly retired

from the challenge.

In parallel with the GPS navigation

offered by my AIS / Navigator unit and the other half dozen GPS devices I had

on board I ran celestial navigation. This comprised a morning sun sight

followed by a noon sight. The reasoning for morning sights was that if I missed

one I had the contingency of an afternoon sight. In practice afternoon sights

are probably better as they give a position line that is perpendicular to the

direction of travel and therefore a better indication of progress. Noon sights

were taken whenever the sun was available and it wasn’t too rough. I clocked up

13 noon sights in 24 days, I also managed 21 sun sights, a moon sight and a

dubious Polaris sight in this time. The main reason sights were not achieved

was cloud cover, also boat motion accounted for a significant number of missed

sights. If I used a GPS derived estimated position then my intercepts were

within 5’ of arc, noon was within 3’ of GPS latitude. I had confidence in my

sights and the calculations. I didn’t even attempt a star sight, there was too

much cloud cover, boat motion made the administration of stars problematic but

I did practice locating and shooting individual stars when conditions allowed.

What wasn’t so good was my dead reckoning work. Monitoring course and speed for any duration was almost impracticable in all but the most steady of weather. As the wind speed and direction changed so much, on average I was changing sail plan 6 times in any 24 hours, that it proved impossible to achieve a dead reckoning position that gave anything better than an intercept of 15’. If I had kept better records of travel and plotted then on a sheet this might have improved the accuracy.

I was able to navigate using

celestial bodies and my 4 figure Reeds almanac tables. With a land fall on

Terceira of 25nm I would have been successful but being on my own and given the

weather conditions I wouldn’t have been confident in my position keeping with

just celestial navigation. I used a pad of universal plotting sheets and this

worked well but had the limitation of the centre fold where a protractor

wouldn’t lie flat. I achieved 13 daily plots but of these only 11 gave a usable

position which was typically around 10nm out from GPS. My assessment of each

plot identified poor DR work as the main cause.

My sextant is one I have had for a

very long time, some arm chair navigator told me it was useless on a boat

because it had the wrong telescope. It worked for me and when it was very rough

I used it without the telescope. My chronometer is a cheap Casio F-91W wrist

watch that I rated over an extended period. It lost an additional 2 seconds

against rating over 25 days of fairly rough water sailing.

Boat Management

Louisa is about 50 years old, she was very well made as far as I can tell and has been well set for offshore sailing by a pervious owner who kept her in the Mediterranean and sailed her on his own. The last owners didn’t appear to do much with her but kept her clean. Most things seemed to be solid but I hadn’t tested her in all of the conditions I was expecting so I was prepared to sail her cautiously. By this I mean with sheets and halyards cracked off a fraction and plenty of windward traveller. By this approach I would loose 5 to 10 degrees of windward performance which would make me slow but there should be shock absorbency inherent in the running rigging. The standing rigging was relatively new with the lowers having been uprated and replaced last year. The mast had been fully inspected by me and no problems found.

To reach a destination, both the boat and crew need to make it there. This philosophy shaped my sailing and approach to on-going boat management. As an example, I checked the bilges regularly for any water ingress. There was some and I thoroughly check the source which turned out to be one of my water holders that had sprung a leak.

On my way to the start the boom attachment for the kicker cam adrift. The boom had corroded through where the plate was riveted on. I re-riveted it on and determined to not load the kicker up fully when off the wind. A cleat on the mast was removed after the mainsail caught it when being raised. I was continually watching for this type of situation and to help reduce chafing I put PVC sleeving over points of contact such as where sheets crossed guard wires.

I had a set of checklists for daily checks and weekly checks which I managed to keep to as weather would allow. As soon as conditions were suitable I would go forward and check all deck fittings and what I could see from the deck. Nothing required attention except the lower shrouds. At around 10 days in I was reefing and leant back against the after lower starboard stay. It seemed very loose, almost as though it wouldn’t support my weight, let alone the mast! I lowered the main sail and reduced the genoa to less than three reefs in size. In the morning, after worrying all night, I inspected the lower stays and it seemed that the aft lowers had lost a significant amount of tension. It was at this time I remembered that the cheap swageless fittings that I had used and planned to replace prior to departure were still in place. I tried to think of all of the reasons that the stays might go slack and all of the ways in which I could monitor the problem and how I could prevent it from getting worse.

After checking the rigging spares I

found all of the parts I was going to use to replace the cheap fittings with:

sta-lok swageless eyes, thread lock, extension shackles. It was all there, I

just needed flat water to fit them. I even had the Loos tension gauge that a

friend had lent me. My strategy for dealing with the problem included setting

the main and genoa sheets so that I could reach them from the cabin to let the

sails fly if anything changed on the mast or rigging. Reefing deeper and

earlier than normal. Running with even more slack in the running rigging to

increase shock absorbency. Marking the aft stays, as these seemed to be the

worst affected, to check for movement. In hind sight this was near on pointless

but worry made me try everything possible to at least monitor the situation. I

found some cable grips onboard and attached these so that they were just in

contact with the top of the swageless fittings. I then lashed the cable grips

to the deck eyes.

Two weeks was a long time to be worried to the point of feeling sick and by the time I was safely in Angra da Heroismo marina and I could check things out I found that the starboard aft lower had slipped a further 1.5mm. The mast had a pronounced rake which it didn’t have when I started.

Also, the grip had twisted in the direction of the thread which seemed to indicate that the wire was slipping out of the fitting.

I replace both of the fittings on the aft lowers which was about 2 hours work. So far the tension has remained constant after around 24 hours sailing between Angra and Velas and Velas to Praia.

Food management onboard was effected by moving a few days supplies of evening meals from the bunk stowage to upper port side locker whenever it was calm enough. For the first week I lived off high calorie snacks as it was too rough to even boil the kettle. Eventually I was able to have a cup of tea and heat some soup up but the cooking arrangements were not going as planned. This got better as time went on and I even managed a corned beef hash which lasted three days and was quite tasty. I knew food wouldn’t be a highlight but at times it was miserable. Towards the end I was able to follow my diet plan but I think I had lost quite a bit of weight. Hydration was a problem early on. I felt sick for the first three days and was having to force myself to drink 2 litres of water a day which wasn’t ideal. I took rehydration salts and vitamin supplements most days which helped.

Clothing became an issue, my carefully packed clothing suffered when one of the vacuum bags leaked so that the contents swelled up and I had to dismantle the bag to get anything out of the locker. By the time I had done this much of my clothing was either damp or in the wrong bag. I made do with very limited changes of clothes until I got to Angra.

Boat cleanliness was an issue as the black mould which I thought I had treated came back with a vengeance. Clothing, sleeping bag, curtains, towel, water proofs were all affected by it and this was quite demotivating. Once in Angra I dried and cleaned every space with bleach solution and used the warmer weather to help dry the boat out. I wish that I had put more effort into this prior to setting off.

Personal hygiene wasn’t great but once I got into my rhythm this improved and the wet wipes and spray bottle worked well. Heads arrangement was standard singlehanded. I was rigorous about brushing my teeth, I mention this because when I was surrounded by dolphins I spat out the spent tooth paste and the dolphins disappeared immediately. This might also work on Orcas and seems a lot less invasive than diesel or bleach that I have seen suggested as deterrents.

Other problems with the boat were

limited to losing the damping oil out of the compass when I fell on it and a

couple of very minor breakages; a mug and a couple of splinters of wood from

the bench slats. Compared to the others I faired very well and it wouldn't take

much to have Louisa ready for moving on.

Communications

Trying to balance keeping people informed, not causing undue worry and pandering to my needs for information was something that I found relatively hard to achieve. A group of my friends were following me, so were my family and these groups and sub groups had different levels of knowledge, interest and worry thresholds. To tackle this I posted public comments through my Garmin inReach Mini satellite communicator that were of a fairly bland and neutral nature. Slamming into a rough sea state was termed ‘bouncy’ and a strong wind became a ‘breeze’. At a personal, one-to-one communications, level I tailored my messages to the individual. Close family was general progress reports and discussions about home life. I only enabled one-to-one messaging for close friends who had some knowledge of offshore sailing. With this group I restricted discussions to those things that they could help with and this was primarily weather. There is a 160 character restriction on any one message and the younger family members, my daughters, worked out how to use this very quickly.

A factor I had failed to take into consideration was that the other challengers would be posting about their experience and while I was posting that it was breezy and bouncy they were fairly close by and saying it was horrendous and that they were either turning round or worried about their boats. Also, I hadn’t considered the thirst for information about the challenge from potential jester challengers. The organisers (primarily George) re-posted my public posts to the Jester Challenge web site and when I got home it appeared that I had been posting public comments daily while the others had been doing so a lot less frequently. Situation reports were also produced and these were summaries of positions reached and status based on public messages. At one point the situation report included a section on my rigging problem. They very graciously toned down the details of my problem when I asked them to as I didn’t want to cause undue worry to anyone ashore. I knew how I was going to tackle the problem and manage it until I could resolve it. I couldn’t see how shore side support could help so decided to restrict who knew what to those equipped to understand the situation. I do appreciate that this was great material for the Jester community but it didn’t fit in with my personal situation.

I took a short wave radio and while this was excellent for weatherfax and for listening to pre-recorded music I didn’t bother trying to tune into broadcast voice services. I made use of VHF communications for collision avoidance a couple of times, once I tried to raise an American flagged passenger ship on VHF as they were on a near collision course. They didn’t answer on either international or US specific channels and in the end passed me less than ½ mile away which is very close in offshore terms. I hope all of those passengers are safe but I didn’t feel that the watch keeper had a clue what he was doing. Other ships responded positively and safely and there was only the one close encounter. AIS made collision avoidance almost too simple for its own good and this was brought home to me when two fishing boats were heading south at 10 knots, neither had AIS active but they may have had their receivers on. It reminded me that AIS was not infallible. These fishing boats were about 400 nm from the nearest land and made no attempt to alter course. There is no way a fishing boat can be fishing at 10knots and these were both stern trawlers who normally fish and shoot / haul nets at around 3 knots.

Other communication systems on board

were limited to emergency systems and I didn’t need to use any of those. I

wouldn’t want any additional systems but I would consider a more formal

protocol so that others could make best use of the messenger.

Motivation

Why do I want to try and sail across the Atlantic? I don’t remember a time when I haven’t wanted to, other challenges such as ‘round the world’ or ‘north west passage’ don’t appeal as much as tackling the North Atlantic and never have. I cannot explain it, but since finding out that it was possible in a modest production boat I have had it in my sights. I was surprised to find out that the number of people who have successfully completed a single-handed passage of the North Atlantic, crossing from the UK to NE USA, passing North of the Azores, is estimated to be less than 1,000 people, a fraction of the number who have climbed Everest. This year there have been around 10 single-handed crossings and this was a busy year for events! There is a reason for this, the route is against the prevailing weather and current. Also, the weather is notoriously volatile with frequent storms and the additional hazards of ice and fog in the North Eastern phase of the crossing.

The Jester Challenge presents an ideal context within which to attempt this passage and my preparations over the past five years were focussed towards the full Jester Challenge to Newport in Rhode Island. I believed I had the right boat and the best opportunity considering my age, health and life situation. I became committed to this year’s event when I got my USA B1/B2 visa which had taken almost 10 months.

I derive a great deal of fulfilment from planning and preparing for sailing trips in my various old, scruffy and cheap boats. Seamanship and prudence coupled with the satisfaction of doing more with less motivates me, as does the post adventure glow of making it home safely. Sailing, meeting people and encountering nature are significant factors in choosing adventures. A specific destination is a secondary consideration to the adventure, I would have been just as happy to aim for Boston or New York.

Getting to the start line was relatively easy as I had started preparations in plenty of time but I was aware that I hadn’t completed a 500nm offshore passage as suggested by the guidelines. Such a passage is not easy to achieve on the East Coast as it is a least two days to a suitable setting off point and then the passage is across the North Sea which is very different to the North Atlantic.

At the start point in Plymouth I was extremely nervous and I am convinced that this stress manifested itself as mild seasickness for the first few days. The first day was a great start but day 2 was a shock to the system. My motivation took a big hit as I encountered the sea state left by the depression that had been stationary off the West Irish coast for a few days. To counter this I retreated and sailed south before I tried going west again. I found it difficult to get into a sailing rhythm and establish a routine. The schedule of taking sun sights and downloading weatherfax transmissions helped with this but I spent much of the time in my bunk reading. In the heaviest weather I hove to, in reality the maximum wind speed was probably force 9 but the sea state was significant, regularly encountering swell and waves totalling 9m with a shortish period between peaks that caused the boat to slam and bounce alarmingly. Although I had the boat under control and safe and I was able to rest, being hove to resulted in no progress or being driven backwards so was a negative factor in my state of mind.

My morale hit a low when I encountered

the second weather system. This was after being becalmed in the bay of Biscay

and making very little westerly progress. A combination of lack of progress,

the tough conditions and discovering a problem with the boat exacerbated the

situation. Whilst I was setting a reef in the main sail during the night I

found that a lower stay had lost tension. Thoughts that went through my mind

were mostly rational but the overriding thought was that I could lose the mast.

With the sails stowed I waited for daylight to assess the situation. All four

lower stays seemed slack but only one seemed very slack. This was difficult to

assess as the boat was bouncing around a fair bit. I determined to try sailing

but under reduced canvas. With a small jib set (about 5 turns unfurled) I

managed to make some progress but I needed to work out how to manage the

situation. Tightening stays in open water, especially when sailing, is very

dangerous as any slack that is taken in can either lead to over tensioning the

rig or accelerate the onset of the problem. As it turned out it was a good

thing that I didn’t apply any addition tension as a swageless fitting was

slipping and adding tension would increase the chances of the fitting failing.

It was at this time that I received a message that for some reason settled my

nerves, gave me hope of a positive outcome and reminded me that I was not

alone. The message had nothing to do with the rigging as I had decided to not

worry anyone with this news until I had a better handle on it. My motivation

improved as I found that I could set sail with an extra reef in without putting

undue stress on the rig. Where normally I would sail with 2 reefs I was now

sailing with 3 reefs. This had two effects; my westwards progress was hampered

as I could only get within 70 degrees of the wind but the boat didn’t slam into

the sea so much. Things became more comfortable but progress towards Newport

became almost negligible. It was at this point that I decided to head for

safety so that I could assess the rigging problem and consider my options.

Closest land was A Coruna in Spain, the Azores was still over 600nm away. I

determined to give it a day of trying to make progress towards the Azores and

then review my plan. Practical steps that I took to deal with the rigging issue

included fitting cable grips to the stays just above the swageless fittings,

adding lashings to the secure the cable grip to the deck fitting, taking the

main and jib sheets into the cabin so that I could release them quickly if I

detected a change. This all occurred around day 10. The worry created by the

rigging situation and lack of progress seemed to make me feel seasick

again.

By day 14 I was 600 nm from the Azores and progress in that direction, although very slow, seemed possible.

I resigned myself to slow progress but when I became becalmed yet again on day 17, my state of mind took a severe dip as the boat appeared to be shaking itself to bits in the slack swell. Ignoring the Jester rules I used the engine to stabilise things and get out of the centre of the high pressure I had ended up in. On day 19 I had the best day of the whole passage. I was surrounded by dolphins in the morning for about an hour, long enough to video them from the bow. Again in the evening I had dolphins, probably the same pod, and they came back after the sun went down. In the dark the light show that their activity generated in the phosphorescence was incredible.

Food was not a consideration in terms of motivation when I was planning the trip. This was a mistake, I took some treats, mainly sweets and hot chocolate drink but they were relatively ineffective in terms of improving morale. Fresh fruit played a part and when the oranges ran out on day 15 I missed this part of my diet. I got bored with much of the food and don’t want to have to eat TVP for a while but sardines are amazing and I didn’t tire of eating them. Knowing what I know now, fresh veg and the ability to cook with them will form part of my future adventures. Corned beef hash was great but the quantities from a standard tin of corned beef made it a bit overwhelming; three meals of corned beef on consecutive days was challenging. Plain water, especially water treated with aquatabs, was hard to consume, the addition of orange flavoured vitamin tablets helped. At the start I struggled to ingest 2 litres of water a day in drinks and cooking. Rehydration tablets were vital and provided a good pick-me-up. The best short term motivational consumable was a nice cup of tea after completing a task such as reefing, navigation, messages etc.

As I approached Terceira I was determined to make a landfall at Praia do Vitoria so stayed up all night hand steering. By day break the wind had got up and the low that was to my North West started heading me so I was gradually pushed south of my intended route. I kept going as the sea state built up until I was south of Terceira and then I headed for Angra do Heroismo, engine on and making 1.5 knots into the wind and waves. This was ideal for arrival at first light. The auto-helm couldn’t maintain a course in the sea state so it was another night of hand steering. When I dropped anchor in the bay at Angra it was with tremendous relief but relatively little sense of achievement. Slowest passage to the Azores that I am aware of, intended destination some 2,500 nm away or 7 weeks at current rate of progress and a problem with the boat. The problem with the boat’s rigging was doubly de-motivating because I had identified the issue before I set off, bought the parts to deal with it but for some reason hadn’t got round to it. Once I had overcome my frustration and embarrassment of this situation it turned into a positive as I had all of the parts onboard to rectify the situation including a Loos gauge to check tension. Morale and state of mind rocketed when I made it onto the marina, people were so helpful and the achievement of an offshore passage had started to sink in but I was exhausted.

If this had been a coastal cruise there were times when I would have dropped the anchor and waited for things to improve, that isn’t an option offshore. I just had to keep on going and this in itself is a mixed blessing as far as motivation is concerned. I was forced to keep going, even if it was to a destination I hadn’t chosen and the thought of turning back or heading to Spain was demoralizing. As it became clear that I wouldn’t make it to the USA but the Azores looked to be a real possibility my motivation improved. There was a day when nothing went to plan, during the day I was both hove to and pushed backwards. I fell over getting back into the cockpit and damaged the main steering compass. To break the sequence I hove to, got into my bunk and slept.

I was expecting the encouragement and concerns of people ashore to have an influence on my motivation. This turned out to be limited and apart from restricting the detail of my situation in my messages there were only a couple of occasions when communications had a significant impact on my morale. Forecast wind speeds were, at times, significant under estimates of what I was experiencing and this was disheartening. At no point did I consider the progress of other challengers or what people would think of where I might end up. Later, I discussed my passage with a very experienced couple who I met in the Azores and they didn’t think I was a natural single handed sailor. Initially this was a bit of a knock but when I analysed it they were correct. More than about three weeks away from people and society exceeded my threshold for isolation.

I was expecting some highs and lows on the trip but not the depth of the low of being ground down by the sea state and the rigging problem. Upon reviewing my log I had one day when everything seemed to be against me and this was a day when I had hoped to make progress but the sea state was such that progress wasn’t possible. I reckon I had three good days out of 25. Day 1 was a great start, day 19 with the dolphins and reasonable progress was the best day. Day 11 was also good as that is when I first considered going to the Azores and I overcame my initial fear that the mast was about to fall down.

Am I motivated to have another go? It

is too early to say if I would attempt the full North Atlantic challenge again

but I would definitely set off for the Azores at the next

opportunity.

Modest and informative, not to mention challenging! Well done Bernie

ReplyDeleteHi John, many thanks, hope to see you around, cheers, Bernie

Deletewell done, sounds like you have a tough sail but learned a lot, you couldn't ask for more,

ReplyDeleteThanks Mathew, may be see you on a future challenge? cheers, Bernie

DeleteI admire your tenacity and honesty, this account is a fascinating read and the way you have broken it down is a helpful aide. Thank you so much for documenting your Jester attempt. Your stoicism is a fine example

ReplyDeleteBrennig Jones

Sadler 32, Good Mood

Hi Brennig, thank you for your kind comments. If offshore, single-handed sailing is something that you are into then the Jester Challenge is an ideal event. Next year's challenge will hopefully start from Pwllheli. cheers, Bernie

DeleteThanks Bernie. It's an attractive proposition but at 32' Good Mood is slightly oversized :-)

DeleteWhile entry is at the discretion of the organisers, there were quite a few over 30' at the last Baltimore challenge. https://jesterchallenge.wordpress.com/jester-baltimore-challenge-2019/

Delete3 out of the 7 in the last Azores Challenge too

Delete